University of Manchester

From graphene to onions

It would be fair to say that the University of Manchester is set to make a very thin contribution to the Rosalind Franklin Institute. Its impact, however, is likely to be enormous.

Professor Sarah Haigh, from the University’s Department of Materials, has been working with the National Graphene Institute to develop technology that can encapsulate water inside extremely thin layers of graphene. The technology – which forms part of The Franklin’s Correlated Imaging theme – has the potential to transform the way biological samples are studied.

“Trying to obtain images from biological samples at scales ranging from metres to atoms, as we want to do in Correlated Imaging, is extremely challenging,” says Professor Haigh.

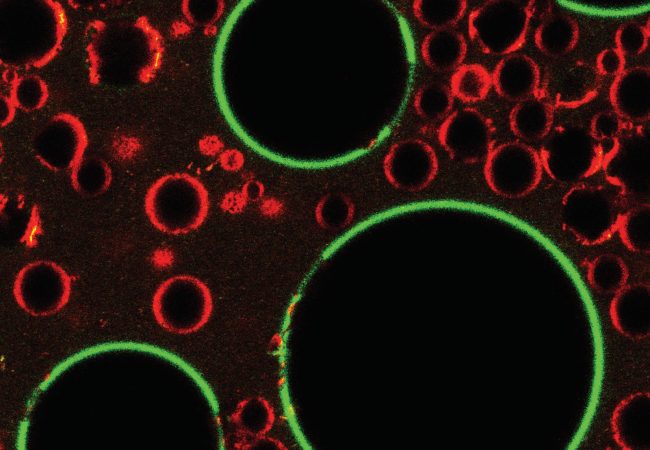

She and her colleagues are creating tiny containers from one of the world’s thinnest materials so biological samples such as proteins can be placed inside suspended in water.

The ultra-thin layer of graphene around the sample is just a few atoms thick, which allows electrons from an electron microscope, for example, to pass through unimpeded. It helps to overcome the need to freeze biological samples in current imaging techniques and means they can be observed as they undergo changes such as those which might occur as a response to drug molecules or in disease.

Professor Haigh and her team have also been working with King’s College London, trialling their Correlative Imaging approach in onions to look at how they absorb heavy metals from the soil as they grow. This has involved finding ways of looking at the onions not only at the scale of the whole plant but right down to the atomic level to see how proteins in the onion cells bind nanoparticles of metal.“

This is a potentially transformative approach,” she says. “While we know how to do it for something like a piece of steel pipe, applying that to a biological system requires some thought.”

Others at Manchester involved in the Correlated Imaging theme at The Franklin include Professor Philip Withers and Dr Timothy Burnett at the Henry Moseley X-ray Imaging Facility, which has one of the most extensive suites of 3D X-ray Imaging facilities in the world and have been using X-ray imaging to help link together the multiple scales of characterization. Dr Katie Moore, from the Department of Materials, who uses a technique known as Nano-Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry to look at, for example, arsenic uptake by crops.

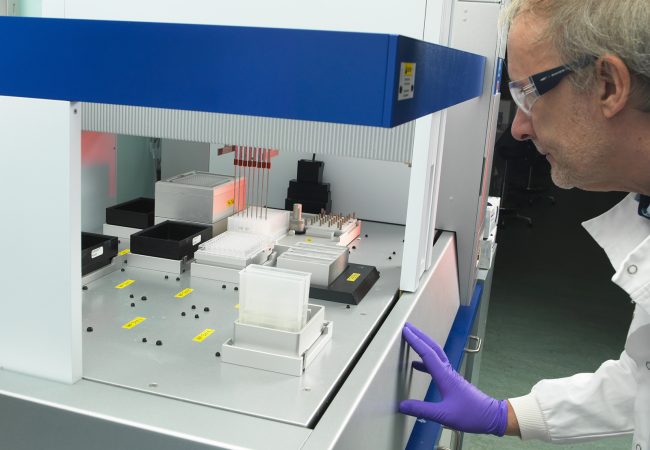

Manchester’s expertise in Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry, or SIMS, will also be contributing to the Biological Mass Spectrometry theme. Professor Nicholas Lockyer, in the Department of Chemistry, is hoping to develop a new SIMS instrument that will use high energy beams of charged particles to ionise molecules on the surface of biological samples.

“By ionising different regions of a biological tissue sample, you can map the distribution of the chemistry across the original tissue,” says Professor Lockyer. “Where different proteins are for example, or where a drug molecule is or different metabolites.

“Building an instrument like this would be difficult through the standard routes as it is a high risk, high reward project. By bringing together the expertise from many different areas, The Franklin gives us the opportunity to meet the challenge.”

Professor Martin Schröder, Vice-President and Dean of the Faculty of Science and Engineering at the University of Manchester, describes The Franklin as an “exciting initiative” due to the way it offers researchers from the physical sciences and engineering to apply their knowledge and expertise to a range of challenges in biological sciences.

“Step-changes in our knowledge and new disruptive technologies in this area can only be developed by bringing together multi-disciplinary teams of scientists to work together in common cause,” he adds.