The Franklin is driving ultra-fast bioscience research at new national facility

RUEDI will enable direct observation of fundamental dynamic structural and chemical processes in real-time.

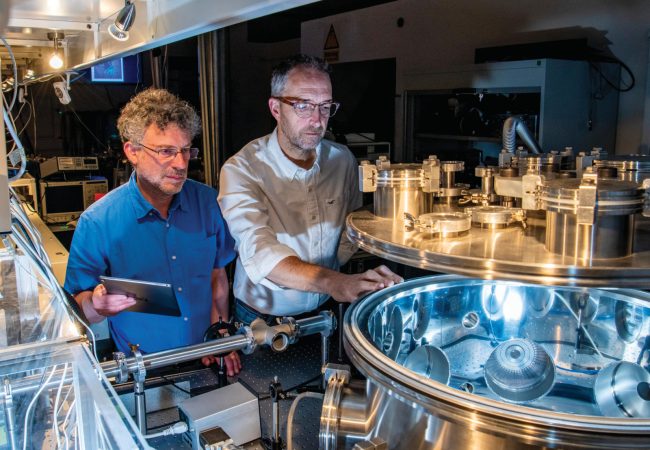

Angus Kirkland, Science Director at the Rosalind Franklin Institute and Professor of Materials at the University of Oxford, and Nigel Browning, Chair of Electron Microscopy at the University of Liverpool, describe how plans to build the £125 million RUEDI (relativistic ultra-fast electron diffraction and imaging) facility are progressing. RUEDI will enable direct observation of fundamental dynamic structural and chemical processes in real-time.

“Reactions in cells and the integrity of materials during explosions are just some examples of the types of systems we’ll be able to see at molecular resolution and femtosecond timescales,” says Browning, RUEDI facility Director.

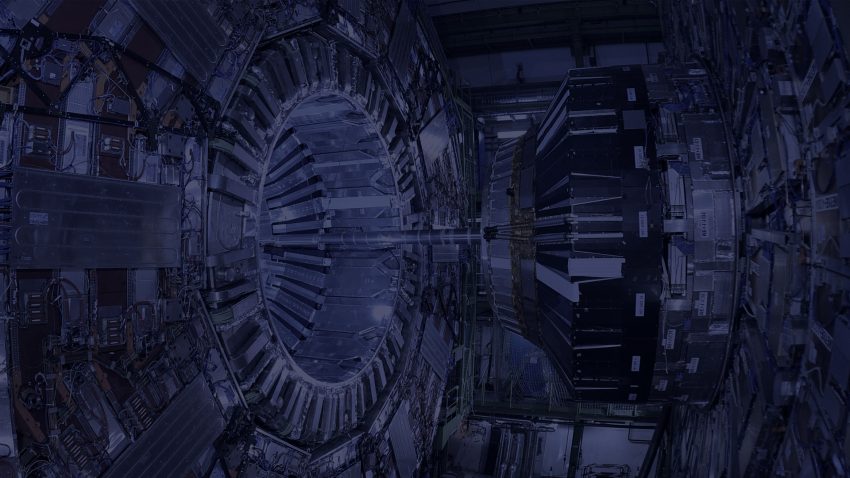

The new facility to be built at the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) Daresbury Laboratory (Cheshire) will combine technology from electron microscopy, high-energy physics and ultra-fast lasers. “All the core technology already exists,” Browning says, “but it has never been integrated to create the unparalleled spatial and temporal resolution that RUEDI will provide.”

RUEDI was first ideated in 2017. Browning had just moved back to the UK from the US where he had been developing electron microscopy techniques for 25 years. Along with collaborators at Daresbury, he wrote a statement to the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) on the need to build a Relativistic Ultrafast Electron Diffraction and Imaging (RUEDI) instrument to be able to measure the molecular motions directing key chemical processes.

Since then, the concept of building a single instrument to work on one area of science has grown into a much bigger instrument that will be used across five research themes – Dynamics of chemical change; Energy generation, conversion and storage; Materials in extreme conditions; Quantum materials and processes; Artificial intelligence; and Biosciences – in what will be a globally unique national facility.

Following submission of the Statement of Need, RUEDI received an Infrastructure Fund Award in 2020 for preliminary design activity. In March 2024, the UK Research and Innovation’s (UKRI) Infrastructure Fund confirmed that it would commit £125 million to building it.

“There aren’t many opportunities to build a one hundred-million-pound piece of equipment,” Browning says. “RUEDI requires bringing together many different types of expertise, which is why the cost goes beyond a normal instrumentation grant.”

Kirkland, the RUEDI Lead for Imaging, is focussing on the imaging part of the construction and the Biosciences theme. As part of RUEDI project team he has been helping to define the capabilities and applications of RUEDI in consultation with the scientific community.

The team are currently working on a business model for UKRI and finalising the design work. The construction phase, due to start in 2026, is expected to take 4 years. “Our next series of Town Hall meetings in 2025 will help refine the immediate science challenges, which will influence the detailed design of the final instruments,” Kirkland says. The timeline for construction also gives the team time to set up training programmes and build up the science themes.

Using RUEDI to advance the Franklin’s bioscience research

Applying physical sciences techniques and methods to address critical problems in biology and biomedicine is at the core of the Franklin’s mission. “Because the design of RUEDI will be tailored for biological applications, it ties very nicely with the Institute’s goal,” Kirkland explains. “RUEDI will be another tool in our armoury to solve key problems that we can’t tackle with current instruments.”

He is particularly looking forward to using RUEDI to address gaps in our understanding of complex, multi-step biological processes that take place at very fast time scales, such as photosynthesis in plant cells and cardiac muscle contraction.

RUEDI will accelerate electrons to more than 97% of the speed of light (with energies of up to 4 MeV) and contain them in ultra-short pulses to give the time resolution required to study chemical reactions as they happen. “In the diffraction mode, the temporal resolution will be very similar to that of an X-ray Rree-Electron Laser (XFEL), such as the Linac Coherent Light Source at Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, but at a fraction of the cost,” Browning says.

Compared to current state-of-the art medium voltage instruments at the Franklin, the time resolution is anticipated to increase by several orders magnitude, with even greater improvements possible for certain types of experiments.

Importantly, particularly for bioscience research, RUEDI will also allow researchers to image samples that are up to tens of micrometres thick. “By using high energies, we can image structure and dynamics in whole cells at temporal resolutions relevant to key processes,” Kirkland says. “This is impossible with lower voltage instrumentation,” Kirkland says.

Imaging biological structures and their transformations in a cellular context will be revolutionary for the life sciences and medicine. “We’ll be able to directly observe the effects of drugs in cells and membrane dynamics, understand how these relate to disease and accelerate drug development,” he adds.

In the coming months, the RUEDI team will continue to raise awareness of RUEDI’s capabilities through online and in-person events, and to build a global research community to ensure the facility meets a broad range of scientific needs and leverages diverse expertise.

Stay updated on RUEDI’s latest developments here: https://www.ruedi.uk/