Franklin researchers demonstrate ‘significant potential’ of llama antibodies as potent Covid-19 treatment

Scientists at the Franklin have shown that a unique type of tiny antibody produced by llamas and camels could provide a new frontline treatment against Covid-19.

The research demonstrates that these ‘nanobodies’ can effectively target the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes Covid-19. Future nanobody-based treatments could be taken by patients as a simple nasal spray.

Short chains of the molecules, which can be produced in large quantities in the laboratory, were found to significantly reduce signs of Covid-19 disease when administered to infected animal models.

The nanobodies, which bind tightly to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, neutralising it in cell culture, could provide a cheaper and easier-to-use alternative to human antibodies taken from patients who have recovered from Covid-19. Human antibodies have been a key treatment for serious cases during the pandemic, but typically need to be administered by infusion through a needle in hospital.

Public Health England described the research as having ‘significant potential for both the prevention and treatment of Covid-19’, adding that llama-derived nanobodies ‘are among the most effective SARSCoV-2-neutralising agents we have ever tested’. The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, which co-funded the research, said the work was a ‘vivid illustration’ of the impact of long-term discovery research of the kind carried out at the Franklin.

Neutralising variants of concern

‘Nanobodies have a number of advantages over human antibodies,’ says Professor Ray Owens, Head of Protein Production at the Franklin and lead author of the research. ‘They are cheaper to produce and can be delivered directly to the airways through a nebuliser or nasal spray, so can be self-administered at home rather than needing an injection. This could have benefits in terms of ease of use by patients but also gets the treatment directly to the site of infection in the respiratory tract.’

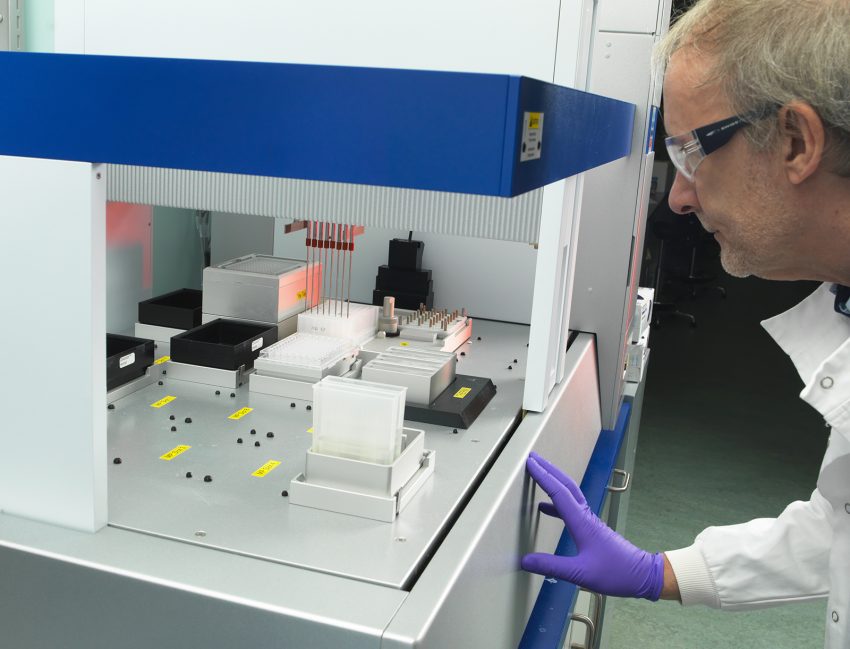

The research team, whose findings are published in the journal Nature Communication, generated the nanobodies by injecting a portion of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein into a llama called Fifi, who is part of the antibody production facility at the University of Reading.

The spike protein is found on the outside of the virus and is responsible for binding to human cells so it can infect them.

Although the injections did not make Fifi sick, they triggered her immune system to fight off the virus protein by generating nanobodies against it. Researchers took a small blood sample from the llama and were able to purify four nanobodies capable of binding to the Covid-19 virus.

The nanobodies were combined into chains of three to increase their ability to bind to the virus. These were then produced in cells in the laboratory.

The team found three nanobody chains that could neutralise both the original variant of the Covid-19 virus and the Alpha variant that was first identified in Kent, UK. A fourth nanobody chain was able to neutralise the Beta variant first identified in South Africa.

When one of the nanobody chains – also known as a trimer – was administered to hamsters infected with SARS-CoV-2, the animals showed a marked reduction in disease, losing far less weight after seven days than those who remained untreated. Hamsters that received the nanobody treatment also had a lower viral load in their lungs and airways after seven days than untreated animals.

A new type of treatment

‘Because we can see every atom of the nanobody bound to the spike, we understand what makes these agents so special,’ says Professor James Naismith, Director of the Rosalind Franklin Institute, who helped lead the research.

The results are the first step towards developing a new type of treatment against Covid-19, which could prove invaluable amid efforts to combat future waves of disease.

‘While vaccines have proved extraordinarily successful, not everyone responds to vaccination, and immunity can wane in individuals at different times,’ says Professor Naismith. ‘Having medications that can treat the virus is still going to be very important, particularly as not all of the world is being vaccinated at the same speed and there remains a risk of new variants capable of bypassing vaccine immunity emerging.’

If successful and approved, nanobodies could provide an important treatment around the world, as they are easier to produce than human antibodies and don’t need to be kept in cold storage facilities.

The research team, which included scientists at the University of Liverpool, University of Oxford and Public Health England, hopes to obtain funding to conduct further research needed to prepare for clinical studies in humans.

The researchers, who were funded by UK Research and Innovation’s Medical Research Council and Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the EPA Cephalosporin Fund, and Wellcome, also hope to develop their nanobody technique into a so-called ‘platform technology’ that can be rapidly adapted to fight other diseases.

‘When a new virus emerges in the future, the generic technology we have developed could respond to that, which would be important in terms of producing new treatments as quickly as possible.’